One of these big questions which arise and is particularly strong in Reformed Theology, is the question of how evil originated. If God created good humans in a good world, and if human action is the result of acting upon one's desires, then how could sin have ever come about? If a good, all-powerful God created a good world, then any deficiency which arises seems to be attributable to God. But Christians know that can't be the case, for then God would be evil.

A few weeks ago I finally started reading through Origen's de Principiis, something I've been wanting to do for quite awhile. Then yesterday, through several of the things Origen said, something just clicked in regard to this longstanding question. While I am not claiming that I have answered the enigma, or even that my thoughts are new (perhaps Origen will address this later, or perhaps other theologians have answered this elsewhere), I am excited at least to have been guided to an answer that I think is viable and has strong explanatory value. Hopefully the concept works and holds up to scrutiny, or at least advances the issue.

Accidents and Essences:

Early on in de Principiis, Origen makes a very important distinction between God and humanity. God is, in his essence, righteous and wise. He is by definition, by substance, and by nature those perfect attributes. Angels, humans, and other created beings, however, since they are not God, are only able to be these good qualities in an accidental sense. By "accident" we simply mean that they are properties which a being can have, but the being is not by definition those things. If a creature is mutable, then it cannot, by definition, be immutably perfect in essence. So when God created volitional beings, the ability to change was inherent in their being. And while they were created in a state which was good, the ability to change meant that they could be corrupted and fall away from the good. God, on the other hand, can never fall from that which is good since he is defined as good and immutably so in essence and nature.

This corruptibility potential for volitional beings meant that in order to be good and holy and all those things which align with God, created beings needed to maintain their good state. Origen provides a hypothetical earthly example of this when he talks about a perfect doctor who knows all knowledge and all procedures in the medical field. The vast expanse of medical knowledge, physical dexterity, and competencies need not be crossed any longer, for the doctor has arrived at perfect medical ability. However, the doctor can lose those skills should he or she stop reading, practicing, etc. God essentially created the angels and humanity in a state where the huge gulf of holiness was already crossed for them in that they were created without blemish and had all good things at their disposal. They were created in a state of goodness where they needed only to continue abiding with God so as not to lose their position.

Forming and Maintaining Desires:

How do you get from good beings who abide with God to beings who are willing to do evil? Where does this corruption come from? In order to understand this conundrum, I want to provide you with an opposite example.

One of the coolest words I learned in my wife's apologetic's program was "doxastic voluntarism." Doxastic voluntarism is basically a questioning of the idea of whether or not we can choose our desires. Can I choose to like coffee or beer or prayer? I would argue that you can't choose your desires. However, you can foster them. Perhaps I want to like coffee or beer in order to fit in socially. I can't make myself like coffee or beer, but I can choose to partake of those things over and over again. Maybe I want to desire prayer like my spiritual mentor does. I can't make myself desire prayer, but I can choose to persist in praying constantly. What we typically find is that while you cannot choose to desire what you don't already desire, you can choose to act in accord with the things you want to desire, and your discipline and actions will create and kindle new desires. This is essentially what spiritual disciplines are. So many of us (myself included) get into ruts where we wait on the desire to pray or the desire to read the Bible, but that desire never comes. What we really need is to act first, and desire will then follow from habit and discipline.

The same process tends to work with healthy eating, exercise, and other sorts of lifestyle choices which are difficult for many people to enact. If you've ever struggled through any of the aforementioned disciplines, you know that getting into the habit is hard, but once you have it, the desire tends to be there and it's much easier to maintain. However, for a variety of reasons, usually involving a break in routine, those disciplines and desires can be destroyed.

I will argue that this second half of the equation is what may have occurred with the first fallen angels and humanity. While they were created in a disciplined state where their desires led them to maintain their good state, a failure in the maintenance of their position lead to a falling away of their first love. While the falling away was evil, the process in which the falling away was not evil, but rather amoral.

Falling Away:

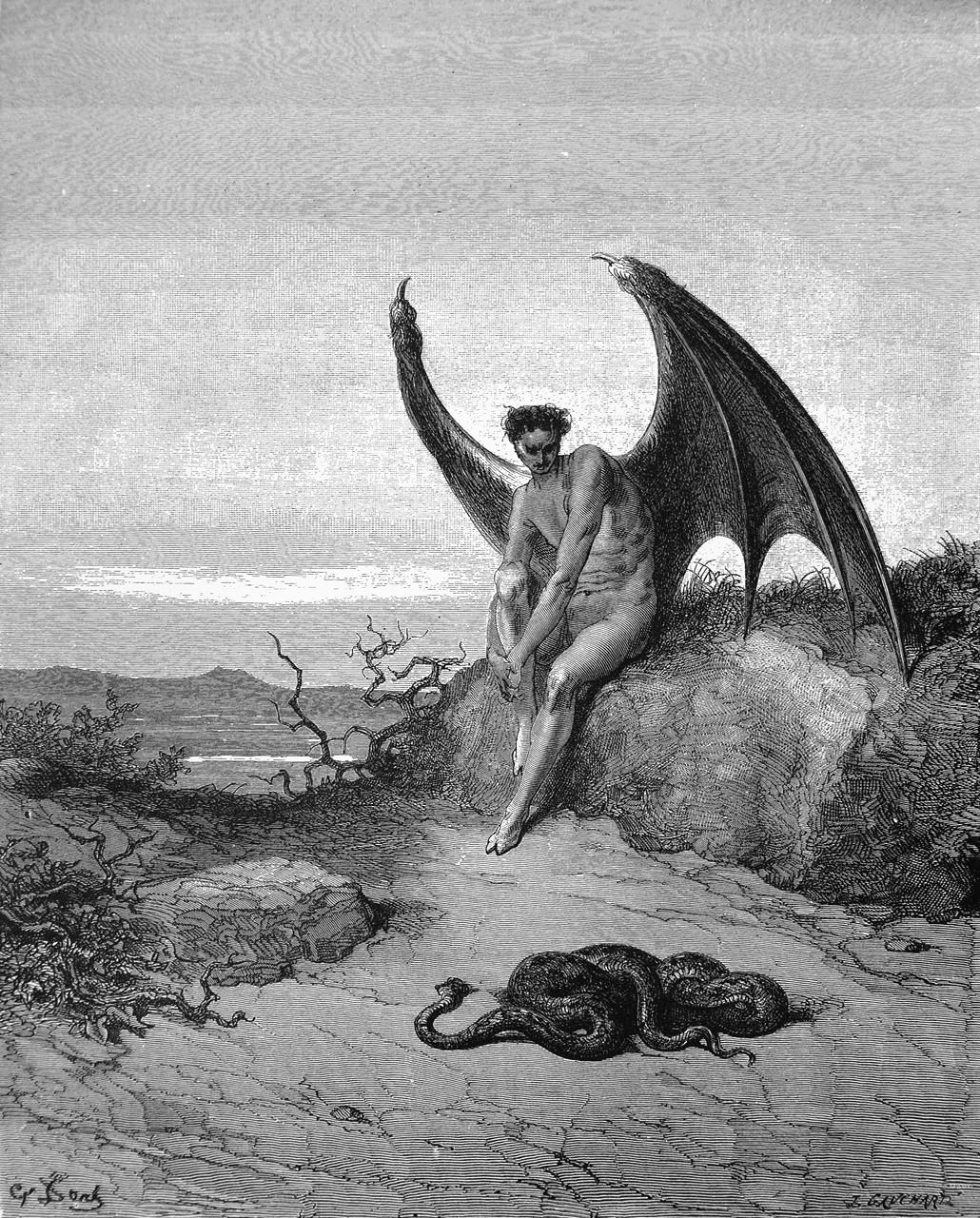

It seems pretty clear that with humanity, there was a specific action for which they were condemned. It seems that the same was also true for Satan, in that there was a moment in time when his pride caused him to seek the usurpation of God's throne. Though we don't get much of a glimpse into the prior thought process of Satan or Adam and Eve, it is intuitive to most of us that sin didn't just manifest itself one day, in an instant. It is more likely that the instance of sin was the culmination of some sort of process which had been going on for some time.

I will argue that the process which led to sin was an amoral process, and a process which is similar to Origen's doctor example. Perhaps the expert doctor woke up one morning and wasn't feeling well and simply decided to take the day off to rest her body. And the day after that, the doctor wanted to spend time with her husband and put off study and practice yet another day for something that was good (her relationship with her husband). It's easy to see how one can move from a state that is good to one that is not over time, through no malicious intent. The same often happens to us when we break our diets, lose our fitness levels, etc.

It is very possible that this is the type of thing which happened to Satan and the first humans. Adam and Eve were created to have dominion over the earth, to love each other, and to love God. And they did. But as Adam spent more time with Eve and less time with God, his desires for the one may have increased while his discipline and desire in regard to the other decreased. Adam's love for Eve was not immoral, and there was no ill-intent involved towards God. Adam was not neglecting God, but was simply fostering his desire for Eve. This desire for Eve was not a warring desire of the flesh. It was not evil. Adam was not idolizing Eve. He simply spent time with her, while his desire for her grew. Then one day, his increased desire for Eve and his decreased desire for God caused him to make a choice which subverted appropriate priorities, leading to the first sin of humanity.

Of course this series of events is hypothetical. I can't prove this is what happened. But it makes sense to me. When God created relational beings who could interact with other relational beings other than God, the potential for the fostering of passions and desires apart from God was created. While many desires are moral or amoral (e.g. Adam's desire and love for Eve, Adam's relationship with creation and attempting to fulfill God's command to take dominion, Satan's relationship with other angels, etc), the desires lead us to morally infused decisions. Such a problem was perfectly coherent to Augustine, who argued that there are generally no passions or desires which are wrong. Instead, the problem of sin comes in when we have our desires wrongly ordered. To love our families, to love animals, to love God, and to love cars are all loves which are perfectly good, but only so long as they are appropriately ordered, with God, of course, at the top.

So how did the first sin come about? How was sin formed in the first sinful actor? It surely wasn't inherent to their nature or essence, for then God, it seems, would be guilty of creating a flawed creation and creating sin. Libertarian free will is also a bad explanation, since such an invocation is groundless and lacks explanation. Did Satan or Adam and Eve sin just because? Because what? Because of who they were (their created nature or essence)? No, that puts sin on God. Just because? No, that's randomness and lacks explanatory power or grounding in one's identity. Sin came about because even in a perfect world, it was possible for mutable creatures to have desires for good things wane and grow, until some of God's good things became ultimate things, and their passions became wrongly ordered, manifesting as sin.

Theodicy and the Problem of Evil:

If God is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent, why then did he not create a perfect world? Doesn't the existence and continuation of evil prove that God either doesn't exist, or that he lacks one of the "omni's?" The common answer to this in modern Christianity is the "free will defense." It is argued that it is logically impossible for God to create a world in which free creatures will always follow him. But I take issue with that theodicy for a number of reasons, the core of which are as follows: 1) libertarian free will boils down to randomness, which is as problematic as determinism, 2) libertarian free will lacks grounding in one's identity, 3) libertarian free will, as most understand it, would make God a being who isn't free, and 4) libertarian free will can't handle well our perpetually sinless state in heaven. For more issues with free will, you can read a few of the articles I've written here, which are just a small sampling of the issues I have with libertarian free will.

While I don't think libertarian free will creates a good theodicy, I do believe the structure of the argument is very powerful. I just don't like the mechanism. It makes perfect sense to me that an omnipotent God can't do the logically impossible (e.g. create a square circle). It makes perfect sense to me that sin may be an inevitability in a world where God creates rational beings. I just can't handle the mechanism being libertarian free will. But if we substitute my new proposal here - that the desires of mutable individuals can be changed (gained or lost) through persistent action (or inaction) - and that as desires change, it is possible to make moral or amoral things inappropriately ordered - then the theodicy holds. God created mutable creatures who enjoyed his perfectly good creation, but through their actions and experiences, lost their desire for God first, and grew other desires which they then ordered to be above him. In this, sin was birthed.

God, then, was unable to create a world in which a desire for him would not wane in some, and inordinate desires for other things would not grow to be above him. A world without evil was logically impossible alongside rational beings. The process leading to sin was inevitable in mutable, rational creatures. Nevertheless, God determined that it was good to create a world where creatures could love him, even though he knew they would also create many evils. God is not responsible for the evil which arose, but in his power, wisdom, and goodness, we know that he will bring about ultimate justice and goodness.

How Will We Not Sin in the New Creation?

Though I think the above explanation has a lot of explanatory power, there is still one nagging question. Can this theodicy explain any better than the free will theodicy this idea that we will remain forever sinless in the new creation? Once again I turn to Origen for a helpful concept.

Origen, along with many of the other early church fathers (and the Orthodox church today) discuss the concept of theosis or deification. This idea sounds foreign to Western Evangelicals because we think it's weird to talk about us becoming like God. It sounds almost cultish. However, we have the same concept, we just call it something softer - "glorification." The church, through the ages, has proclaimed that when restoration is fully realized, we will be made like Christ. This isn't simply because God zaps us to be different than we are now, but that through the Holy Spirit (and a lot of mystery), we are actually partakers of Christ. We are joined to him. The discussion here would be very long in order to identify what is orthodox and how this is distinguished from pantheism (for example, we retain our identity on Christianity), and that isn't the point of discussion here. You simply need to understand that deification/theosis/glorification is standard Christian teaching.

This concept is important for the topic at hand because Origen makes an vital distinction between humanity's created state and God's eternal state. Whereas humanity was not in essence or nature holy, God is by essence and nature holy (and all other good and perfect things). Whereas humanity's goodness is mutable, God's goodness is immutable since it is grounded in his essence/nature. The concept of deification/glorification recognizes that pantheism is false and would condemn as heretical its conception that we will ever be like God in our essence - for to argue such would be to argue that we become God. Instead, the early fathers largely argued that we would become like God in our energies. What exactly are energies? Again, this is a complex topic which needs much more discussion to parse out, and this extended discussion is not the scope of this article. The point is simply that we will be deified in some fashion - a fashion in which God remains God and we remain ourselves, yet we are enjoined to God in some mystical way.

This enjoinment to God is what is vital for our persistent sinlessness in the new creation. Since God is immutably good, the enjoinment of us with him means three main things. First, as Christ is joined to us we are imputed his righteousness. Second, it makes us partakers in the immutable goodness of God. And third, through God's Spirit who resides within us, we will never take a step away from the presence of God. Whereas God, in the Garden, walked with Adam and Eve at some times, and not others, we will forever be in the presence of God in the new heavens and earth, and his very presence will reside within us.

Of course this raises all sorts of other questions in my mind, like if God's presence in us is what keeps us holy, why then wouldn't he have just filled Adam and Eve with his presence form the beginning? I'll have to think on that one, and many others. Sure, there are still questions, and there always will be. But at the moment, I think Origen and Augustine have helped to put together an explanation of the first sin, a theodicy, and an explanation of persistent, deified sinlessness in heaven. And I think it has more coherence and potential than most alternative explanations.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed