It shouldn't at all be a surprise to Christians that our intuitions would be wrong on the issue of violence. Consider Greg Boyd's words below.

I would argue that disciples should expect the NT’s revelation of God to violate our commonsense intuitions. After all, we are commanded to imitate God, who as a human gave his life for us while we were yet enemies (Eph 5: 1–2; cf. Rom 5: 10). As Paul conceded, to the “natural” mind, which is always “hostile to God” (Rom 8: 7), nothing could seem more “weak” and “foolish” than the proclamation that the omnipotent Creator chose to let himself get tortured and executed on a cross by enemies, out of love for enemies (1 Cor 1: 18–25). And so, if we are imitating this God in how we respond to enemies, it cannot help but appear “weak” and “foolish” to the common sense of the world. In this light, one could argue that the commonsense intuition about justified violence is proven wrong, from a Christian point of view, simply by virtue of the fact that it does not strike anyone as “weak” and “foolish.” Conversely, one could argue that any response to enemies, and any conception of God, that does not look “weak” and “foolish” to our commonsense intuitions about justified violence are thereby proven mistaken from a Christian point of view."

So if Christ's counterintuitive life, proclamation, and prescription isn't enough to convince you that our intuitions are mistaken about violence. Consider then a more empirically tested attack against our intuitions. The perfect counter-argument against the intuition argument for violence is to show that our intuition is actually built against violence - even in a war which is viewed as justified. S.L.A. Marshall, a Brigadier General in the U.S. Army, wrote an interesting book ("Men Against Fire") on soldiers who refused to shoot at the enemy. Even those soldiers who decided to shoot would often aim to miss. Such a fact was noted as far back as the Napoleonic era and during the American Civil War. You can find out more about some of those examples in another book entitled "On Killing." Marshall's work is what lead the armies of the world to change the way they trained. As one example, the army used to use circular targets for practice, now they used human silhouettes. The army realized that to get people to kill other people, they needed to behaviorally condition them to do so, as our intuition is that we should not kill. While Marshall's statistics and methodology are questionable, the fact that there are a good number of soldiers through history who refused to fire on the enemy (pre-professional soldier era) is evident. Marshall's research, as well as the research of others, brings into question what our intuition on killing actually is. It's easy to say we'd kill an aggressor, but when our armchair intuition is put to the test, our natural intuition seems to lean more pacifistic.

In an article entitled "The Sacrifices of War and the Sacrifice of Christ," Stanley Hauerwas makes a profound claim that I think only a pacifist (or one who viewed all killing as immoral) could make. Hauerwas discusses how the stress of soldiers isn't simply that they put their own lives and wellbeing on the line - as if that weren't enough. But perhaps an even more weighty sacrifice is their sacrifice of the refusal to kill. Now we could speculate all day long about what influences impact veterans and to what extent, but I think there is much more to the sacrifice of a refusal to kill than there is to a willingness to lay down one's life. A willingness to lay down one's life unites soldiers with their community. They are praised for it. They receive medals for bravery. It is an investment they put on the line which gives them buy-in to their community as well as status. But to kill - or even to constantly be in a situation where one knows that they would willingly take human life without question - isolates. Hauerwas provides a number of examples of this in his article. And it is isolation which is so often the motivator for suicide, not community. I think Hauerwas's hypothesis of the sacrifice of the refusal to kill has huge explanatory power for why about three times as many veterans now commit suicide each year than those who died in our twenty years of conflict in Afghanistan. It helps to explain how in 2012 the United States saw more active duty suicides than active duty combat deaths. Maybe Hauerwas is wrong, but I think his view provides strong explanatory power.

Beyond competing intuitions of pragmatism and nonviolence, we can also see that Christ, at times, works against our intuitions. Even if I gave the non-pacifists the benefit of the doubt and agreed that our only intuition is that we kill to defend self or others, this intuition wouldn't be weighty enough by itself. Just take a look at the early church. They seemed to look at things differently. First and foremost, pragmatism didn't seem to be their metric for judging actions. Obedience and love were their metric. If Christ said it and if Christ did it, then who am I, a servant of Christ my Lord, to put myself above obedience that follows him in like fashion? It wasn't until the mid-300's or so, a time that corresponds with Christianity becoming legal and then the state religion, that we see Christianity throw off the pacifistic notion of peace. Why might that be? I believe it is because as the numbers of Christians grew and as the state began to identify as Christian, the state recognized that armies and national defense wouldn't work too well if the populace weren't allowed to kill. If the church was to be married to the state, you had to explain away Christ's teachings and the first several hundred years of teaching on peace. When you couple this with the fact that Rome was losing it's might, the bias and motives of just war formulation become more suspect. It seems a bit too coincidental that the man largely responsible for popularizing the discussion of a just war lived during a time when Rome received its first sacking in nearly 1,000 years. Augustine surely knew Christian pacifism would hamper the formation of armies, and he knew that Rome was weaker than she had been in awhile, and her enemies stronger now than they had been for quite some time. I don't think Augustine's creation of this just war notion was malicious. I think the rulers genuinely feared for their people and the preservation of the great society that had been created. The idea of a "just war" wasn't created in order for the state to assert power and conquer other countries, but to protect. That is noble. But I think it was misguided.

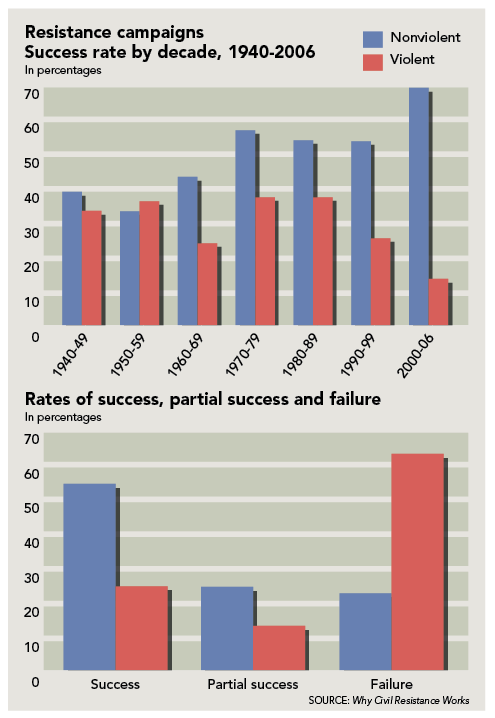

After a couple millennia of instituting "Just War Theory," a practice which attempts to align our fallible intuitions with our Christian convictions, what have we discovered? Surprisingly to non-pacifists, non-violence has proven itself more effective at exacting meaningful change (see also "Why Civil Resistance Works"). The chart below displays what an originally non-pacifistic researcher and scholar discovered as she studied violent versus non-violent revolutions. While this effectiveness is not what makes pacifism correct, it is a wonderful encouragement that we can trust God and we should be faithful to his teachings. His ways are wiser than ours. Who knows what our world would be like now had we adhered to the convictions of the early church, who clung to Christ's teachings wholeheartedly, willing to lose their very lives for obedience to him.

The circumstances surrounding the formulation of what would lead to Just War Theory are interesting, and I'd challenge you to take a look at that. But that is a huge discussion that I don't want to continue here. Rather, I want to look at the main motivation for not embracing pacifism - the intuition that pacifism is just too idealistic. Pacifism is believed by most to be an impractical means, and one that couldn't be truly lived out. Stanley Hauerwas, perhaps one of the most famous modern pacifists, wrote a fantastic article where he flips the charge of "idealism" back on the just war theorists. Most claim that pacifism is unrealistic, but how realistic is the notion of a just war? Is it really any more realistic than pacifism? More importantly for the Christian, is it any more moral and obedient to Christ to engage in a "just" war? Let's take a look at the structure which must take place for a war to be just and ask some questions about how such a thing might occur.

Just Cause: According to most iterations of the theory, there are two just causes. A state can wage war for reasons of national defense (of themselves or an ally), and a state can wage war for humanitarian reasons.

What kind of trust do you have to have in the leadership of a nation in order to do harm for them? If they say a country has weapons of mass destruction, what evidence is required before you can commit to war?

*What kind of virtues would the people of America have to have to sustain a just war foreign policy and Pentagon?

*What would an American foreign policy determined by just war principles look like?

Just Peace: This is a newer addition to just war theory. We are working on this idea that we must be moral in our dealings after peace. We have seen the results of a conquering "peace" when WWI lead to WWII, and we have seen the humanitarian crises and unstable governments wars have left behind.

If you have enough resources to wage war and stop the immediate threat, but not bring just peace following the war, should you still go to war? Is the misery of the other's post-war populace worth saving the lives of some in your nation?

Legitimate Authority: Christians have historically viewed the state as the entity which can wage war, though that was very muddied throughout the middle ages.

Many wars throughout history have had very murky bases for "just cause." A number of wars didn't have a clear aggressor or party at fault. Since God gives all government the right to bear the sword, should a Christian really fight in such a war on a particular side just because he's fighting for his country?

Proportionality: The violence you deal out must be in proportion to the violence you receive, or the potential violence your enemy has threatened. For instance, I shouldn't use mustard gas against you unless you use it on me (or I'm pretty sure you will). Obviously we have the Geneva Convention now which outlaws the use of gas, but this isn't something just war theory necessarily forbids (assuming the other requirements are met).

Was it justified for the U.S. to use nuclear weapons on Japan to save significantly more U.S. soldiers? When you consider the bombs were dropped on civilians, does that change?

Necessity: War must be a last resort. All other options must have been exhausted before pursuing war.

*How would those with the patience necessary to insure that a war be a last resort be elected to office?

Civilian Safety: Non-combatants must be preserved.

We don't fight on battlefields anymore, so war today almost always involves a large loss of civilian life by direct fire or as collateral from losing food, shelter, etc. Is this justified?

Blockades have been popular during war. You essentially cut off all supplies going in and out of a country. While a blockade prevents raw materials from getting used for military purposes, it almost always hurts the civilian population by keeping out food and resources they need to eat, make money, shelter, and live their lives. Are blockades justified?

*What kind of training do those in the military have to undergo in order to be willing to take casualties rather than conduct the war unjustly?

You'd be hard pressed to name any war in history that was even close justified on all these grounds. WWII doesn't even come close to fitting this, as it began due to a failure of "Just Peace" and lack of concessions from the WWI armistice. It failed the "legitimate authority" factor in countries like France where guerilla warfare was encouraged and appreciated by the Allies even after the French government conceded its authority. It failed the proportionality test with the use of atomic weapons. It failed the "necessity" or "last resort" criteria because the war almost certainly could have been avoided if the allies of WWI would have made some concessions and sought peace with Germany rather than conquest. And it miserably failed the "Civilian Safety" factor as civilians were often indiscriminately bombed, or excuses of military targets in the vicinity were used to justify all the civilian deaths. The firebombing of Tokyo alone (which was worse than the use of the A-bomb) killed hundreds of thousands and left over a million residents homeless.

But the failure of implementing a “just war” doesn’t mean that a war shouldn’t be waged with the intent of being just. However, I would argue that in our modern era, with the weapons we have at our disposal, it is impossible to wage a just war against a comparable, unjust enemy. As a case in point, take a look at the Cold War. Both the United States and Russia were poised to attack each other with nuclear weapons – weapons that would have indiscriminately taken the lives of countless civilians and innocent non-combatants. Our country was willing to do that. However, if we would not have been willing to be unjust in our indiscriminate, mass killing of innocents, then we would have had no hope of defeating an enemy who was willing to be unjust in doing so. To go to war with an enemy with no chance of victory would also make the war unjust. Such a forced compromise and an impossibility of justice in war began with the use of gas in WWI, and only grows as technology advances. Today, it is impossible for us to go to war with an unjust foe of equal (or near) stature. In fact, it is likely impossible for us to fight a just war against any country who is willing to use nuclear weapons against us, and has the means to do so.

If pacifism is idealistic in that it will never overcome evil and will inevitably allow evil men and women to run the world, can we let such idealism become a reality? Perhaps not. But what is the alternative? A "just" war? An ideal where rather than letting evil run the world, we harbor and embrace evil and injustice ourselves so we can see "justice" now and ensure that we have slightly more control, ease, pleasures, and freedoms? Pacifism may be idealistic in that it won't preserve the body. But it preserves the soul. A "just" war may preserve the bodies of some of our countrymen and women, but it does so at the cost of marring our souls. I have yet to hear of a just war. They just don't happen, and in some circumstances, are absolutely impossible even in theory. It's an ideal. If we can live with an ideal that can't be realized – an ideal which turns our hearts towards evil - why can't we embrace an ideal that can't be realized and turns our hearts towards love - even love of our enemies?

1. Introduction

2. Biblical Teaching

3. Biblical Examples

4. Early Church Teaching

5. Real Life Examples

6. Pacifism Applied

7. Evaluating the Christian Alternative to Pacifism

8. Pacifism Quotes to Ponder

9. Counter-Rebuttals

10. Questions for Just-War Adherents

11. Conclusion

12. Resources

RSS Feed

RSS Feed