I initially thought Pascal's wager was brilliant. It made perfect sense to me. You should obviously see that in the risk/reward analysis, it is way better to believe in Christianity. However, after some years, Pascal's Wager left me with a very bad taste in my mouth. As I thought about it more and as I listened to atheists speak more (rather than just listening to my Christian community), I recognized several problems I had with Pascal's Wager, at least as most Christians were using it.

1) It emphasized intellectual assent without consideration of Lordship theology and assent of actions.

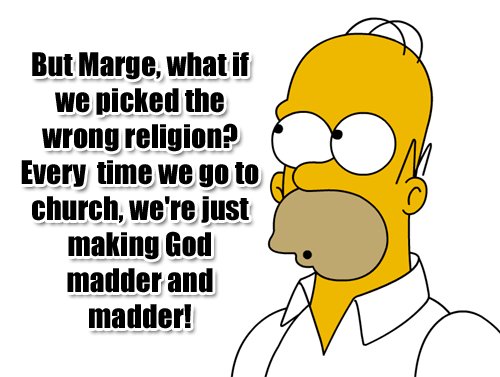

2) It didn't narrow one's choice down to Christianity, as there are other religions which have eternal judgment as a possibility from which one would want to escape.

3) It emphasized potential risk while dismissing (or not accounting for) probability. For example, a large bird could drop a heavy stone on my head from hundreds of feet and kill me, yet I don't, and won't, walk around with a helmet knowing there is a huge consequence should the event occur. The probability of its occurrence is practically zero. Falling out of bed is another example, as it kills about 450 people in the U.S. each year and injures close to 2 million, yet most of us take minimal precautions.

But recently, as is my custom, I've begun to bring my pendulum back the other way and realize that Pascal was on to something we all recognize as legitimate, whether one is an atheist or a Christian. In the remainder of this post I want to explore three ways we recognize that the metric of probability is overrated (and even distasteful), and how at least one of these areas can turn Pascal's Wager from fire insurance to Lordship Theology.

1. Kuhn's Paradigm Shift

Thomas Kuhn is most widely known for his book "The Structure of Scientific Revolutions." It is in this book that he coined or made popular the now common term "paradigm shift." Kuhn's book provides fascinating insight into how science changes over time, and why it changes as it does. Kuhn essentially argues that scientists do not change their views when the evidence crosses the threshold of probability. When the probability of a new theory reaches 50.001%, scientists don't change their minds. They don't even change their minds at 51%, at 55%, or at 60%. To overturn current scientific thought - to create a paradigm shift - the probability of a new theory being true needs to have a relatively high degree of certainty - 70% or higher, depending on the scientific community and what it is we're overturning. From my recollection (having read the book about a decade ago), Kuhn was not critical of this process, as it was an important trial by fire or a vetting process for new theories.

Many scientists and philosophers recognize Kuhn's work as brilliant and insightful. They know he's right and they don't disagree that it is or should be otherwise. In this manner, most people (scientists, atheists, and Christians alike) recognize that overturning tradition is not done upon a 51% certainty, but requires much higher proof than that. We can see this not only with scientific theories, where inertia is a good vetting process, but we see it also with how difficult it is to overturn injustices in the political sphere (like slavery, changing voting rights to include women, etc). Tradition requires a very high degree of probability to overturn. While this inertia can be a huge problem when dealing with significant, ingrained injustices, it also helps to ensure that the positives of our society and our day to day stability aren't whimsically overturned. We understand that certain probabilities need to be higher than 51% for us to act, and we are generally in agreement that it should be this way.

2. Social Ramifications

The second instance in which we recognize the need for higher probability is when a belief change would have social ramifications for us. If I am a Muslim, my family is Muslim, and my community is Muslim, then converting to Christianity has huge ramifications on my life. If I am a Christian pastor, my family is Christian, my community is Christian, and my income is tied to my Christianity, then conversion to atheism would require a higher than 51% degree of probability. At some point we could call someone a sell-out to intellectual honesty for refusing to convert and deal with the fall-out, but I don't know anyone who would place that threshold at 51% certainty. When the people who you know and trust most believe something, and when changing your beliefs would have a negative impact both on you and the ones you love most, the probability threshold is raised significantly.

3. Weight of Hope

I was always fascinated with those crime stories in which a child was abducted, yet the parents spoke as if their child was alive for months. To me, it always seemed clear after two or three days missing that the child was almost certainly dead. And after a few months, while the parents were still acting as though their child might be alive, their hopeful thoughts and actions seemed irrational.

Now that I have my own children, I empathize much more with those families who have gone through this process. It wouldn't matter to me if the police told me that there was a 99.5% certainty my child had been killed, so long as there was an ounce of hope that my child was alive, I would hope it and pursue rescue. Of course there is always a threshold. Some parents may resign to what is likely reality after six months, some a year, and others five years. But needless to say, a parent's resignation to what probability indicates is far more than 51% certainty.

We see a similar idea in movies like "Avengers," where there is only one possible world out of millions or billions where the heroes can succeed, yet they proceed as though they were living in the one very improbable world. We understand that hope and livability and a clinging to love are things which influence our probability threshold. We may intellectually assent to the probability of our wrongness, but we nevertheless live out the improbability - as the alternative would be to become the walking dead in the present.

The New Wager

Let's return now to Pascal's Wager and see if we can tweak it to fix some of the problems I had with it. Note that for this fix, I am going to largely be drawing from point number three above.

We all live with beliefs which would be hard to live without - the existence of love and free will being two of the biggest. At their core, these beliefs are almost cherished necessities - fuel that makes life run. These aren't mere traditions we are propping up. The overturning of these concepts would have serious ramifications. Their dissolution would destroy many of us. If we truly believed that love and free will did not exist, and if we truly lived as though they don't, most of us would die a thousand deaths. [See "The Death of Love" for more discussion]

I will argue that free will and love are both hopes which give our lives weight. They are like children, who, if abducted, we would search for, long for, and await with expectant zeal. The probability threshold required for us to loose our tight grip on these invaluable features of existence would be near to 1, if not 1 itself. In a world where perfect certainty is impossible, many of us would yet still require it in order to overturn our hold on love and free will.

This is where my proposed "New Wager" is different than Pascal's wager. Whereas Pascal's Wager typically requires someone to seek the avoidance of some judgment which may itself not be true (the avoidance of going to hell), the New Wager emphasizes a continued clinging to that which one intuitively and experientially knows in their core (love and free will). Whereas Pascal's Wager asks us to discard notions of probability to avoid that which isn't intuitive, the New Wager declares that we ignore probabilities (or raise the probability threshold) in order to maintain that which we intuitively "know" to be true and for which we hope above all hope is true.

While materialistic naturalism may seem more probable in the minds of modern atheists, it is important to recognize that probability alone is a bad determinant for belief and action. Thomas Kuhn and the scientific community recognize that, converts who have major ideological shifts understand that (whether religious, political, philosophical, or whatever), and those who have dearly loved ones recognize that. As materialistic naturalism asks us to throw off so much, its burden of proof lies well beyond 51%.

The New Wager doesn't resolve all of the problems I mentioned having with Pascal's Wager, though I think it pushes one to dig much deeper than fire insurance. Naturalists may want to call the New Wager intellectual dishonesty. They may view it as just a weak crutch - a claim I have written about as being a failed, pejorative quip. But I call it a longing of the soul for a world made right. That longing, as Lewis, Chesterton, and others have explained, fits so well if we truly do have a creator who loves us and is in relation to us. So while we are holding out all hope that love and freedom are real, our Father holds out the desire for us to turn to him in repentance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed